By Mehru Jaffer

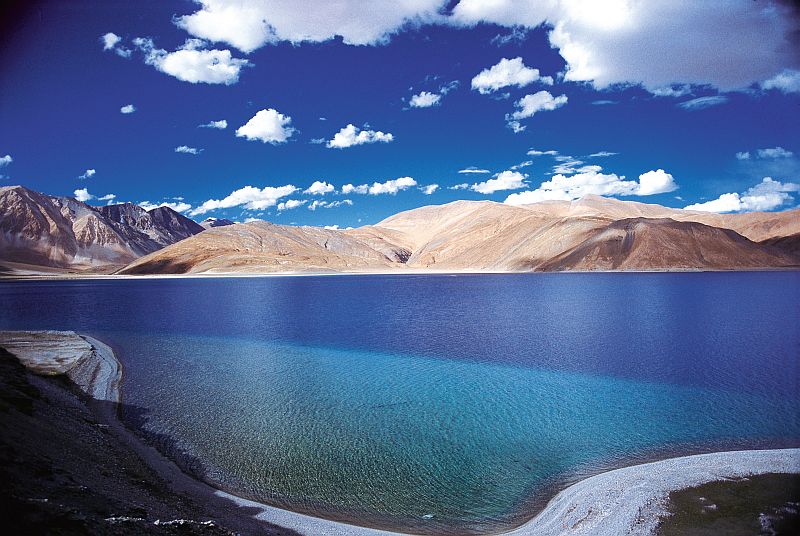

Wherever a temple, mosque and church are seen to share a wall that place deserves veneration.And recently I found a similar space in faraway Ladakh. As I stood in downtown Leh soaking in the sacredness of the place below a canopy of a peacock blue sky, I wondered if it is because Ladakh is nestled in the bosom of the Himalayas, the world’s highest mountain range which makes people there closer to God?

At least the Ladakhis seem to live in a more godlike manner than some of us here on the plains who insist on whiling away precious time murdering each other on the pretext of giving protection to mandirs and masjids. It was indeed extremely pleasant then to spend a few days at Lehs Mogol Hotel recently, so called as it stands on the very terrain where representatives of Mughal India it is believed had camped several centuries ago to extract their due from Buddhist kings.

Namgyal Wangchuk Kalon, the young manager is Buddhist but his mother is a Muslim. “Religion was never a big issue in our family. But good behaviour was always, says Wangchuk as he looks back upon his childhood in Ladakh, an area that has never been monolithic. The landscape here has enormous variety with different mountain peaks jutting towards the heavens at a various range of altitude. The environment is harsh and yet people of Tibetian and Indo-Aryan descent have made the place their home for several thousand years.

It is perhaps being aware of the essential fact that all Ladakhis share a common history and hardships which continues to make people feel close to each other to this day. It also helps that with slight variations in different valleys of Ladakh, the language too is common here.

As far as Janet Rizvi author of Ladakh Crossroads of High Asia is concerned there is indeed a single basic culture of which Buddhism is the bedrock. A historian from Cambridge University, Rizvi lived in Ladakh while Sayeed Rizvi her husband was Development Commissioner. In her enchanting book bought from a mild mannered Sardarji at the Book Worm store, Rizvi rightly raves about Ladakh’s secular culture despite the fact that it is one of the last regions where Tibetian Buddhism is still practiced in its original setting.

For the majority of Ladakhis Buddhism is of prime importance and the small minority of both Shia and Sunni Muslims along with its Christian community are apparently not entirely untouched by the adorable Buddhist values of tolerance and compassion. Yet it is also true that there is much more to Ladakh than just Buddhism.

Lying on the edge of Tibet, high altitude Ladakh is unique for its semi desert complex of mountains, valleys and plateaus and has served as a colourful stage for international trade for eons, making Leh cosmopolitan much before academics learnt to spell the word multiculturalism. The earliest people here were pagan nomads who lived off herds of cattle including the Himalayan ibex that is responsible for the special wool used to make the famous pashmina shawls. The settled population later made trade its most important activity, encouraging immigrants to crisscross the area at will and giving its population a very mixed racial composition.

It is the Mongolian high cheekbones matched by a nose even prettier than the Kashmiri that perhaps makes Wangchuk so dangerously good looking. Seldom does his closed eye smile leave the face as he talks. Wangchuk says his life is only enriched as he enjoys celebrating all the festivals of India. He does not remember his parents ever quarrelling in the house over religion. Maybe because his Muslim mother is one of the first women in Leh to have attended university or maybe it was the bohemian lifestyle of his father who worked for the Indian army that makes Wangchuk continue to rhyme with all sorts of people from around the world.

Apart from getting him good business his hospitality and warmth attracts many even to barren and climatically cold Leh. One of the most colourful members of Wangchuk’s staff is Vijay, a Bengali from Varanasi who obliged me with a generous discount at the hotel only because he said he was seeing someone from so close to Varanasi after so long.

Thanking Vijay I stepped out of the hotel for an aimless stroll down the curvaceous Changspa road to bump into a palmist whose profile resembled paintings of Jesus Christ. He had fled Germany 25 years ago to find his true self in India and in the process got involved with stuff impossible to see with the naked eye.

Studying the lines on my outstretched palms with the end of a delicately carved flute, he declared me to have been an empress in my previous life and warned me to avoid people in this life with negative energy. So I raised my nose a little higher in the air and walked away with an imperial smile plastered on the face, determined to look the other way if I ever saw Praveen Togadia or Osama bin Laden walk towards me.